Sherborne and Yeovil Mercury, dated 14 June 1773.

Ran away last Monday, from his master, Francis Pyle, of Tallerton, in the county of Devon, Richard Wellington, his apprentice. About nineteen years of age, five feet eight or ten inches high, in his walk stoops a little forward, and bends his knees inwards; straight black hair, and is of a tawney complexion. Carried off with him a light coloured drab coat, let out by the sides, very short, with yellow metal buttons, an old scarlet waistcoat, and a dark colour’d coat and waistcoat, with yellow buttons, figur’d; had in his shoes, when he went off, a pair of double ring’d brass buckles. – Whoever harbours or employs the said apprentice after this notice, shall be prosecuted as the law directs. Or whoever shall bring him to his said master, shall receive a Guinea reward.

Well I’m intrigued, and I bet you’re wondering where the rebellious, raven-haired and pigeon-toed Richard WELLINGTON fits into the family tree.

Richard’s parents were John WELLINGTON (1727-1759) and Sarah LEY (1729-?) who lived in Talaton, Devon in England. I don’t know what John did for a living, he may have been a farmer at Talaton – a small rural town about 20 kms north-east of the port of Exeter and approximately 10 kms west of Honiton.

John and Sarah WELLINGTON had 4 boys (John 12, William 10, Richard 5 and Simon 3) and Sarah was again “with child” when her husband died in early November 1759 at the age of 32. His death must have been a devastating blow to Sarah who gave birth to another son Michael in April 1760. With a family to support she would have found life difficult even if they had freehold land and John provided for her and the children in his will.

Their eldest son John was 12 and probably still at school. As first-born he may have been received a sum of money in his father’s will to secure an apprenticeship with an apothecary in one of the larger towns in Devon or Somerset.

Craftsmen usually took on apprentices at about 13 or 14 years of age, although it was not uncommon for children as young as 10 to be indentured in some trades and the term of the apprenticeship was commonly 7 years or until the child reached the age of 21. Masters required a premium to be paid by parents for securing their child’s livelihood. A father’s early death could mean a low premium and poor trade for a child of prosperous parents if provision was not made in the man’s will.

Premiums paid in trades in the mid 18th century varied greatly depending on where the business was – boys bound to London apothecaries had premiums of between £150 and £200 while provincial masters took £50 on average.

Examples of the range of premiums paid to various trades circa 1750:

- £10-£100 – stationer, printer, bookmaker

- £20-£200 – apothecary, attorney, hosier, jeweller, draper

- £30-£100 – Ironmonger

- £50-£100 – artist, coachmaker, conveyancer, sugar baker, timber merchant.

A high premium did not ensure comfortable living conditions for the child. It compensated the master for an apprentice’s errors made as a novice; it provided a child with food, room and basic board in the master’s house or workshop, instruction in a profitable livelihood, and established him in a prosperous career with appropriate marriage and social prospects. Apprentices weren’t paid for their work, except occasionally in the last years of their apprenticeship.

The following is an extract from a parish apprenticeship indenture dated 1 October 1694, at Stockleigh English, Devon. The apprentice could well be an earlier ancestor:

Between Richard Moorish, Churchwarden, Thomasine Bradford, Widow, and William Quicke, Overseer, of the one part, and Henry Bellow, Gent, of the other – binding Susannah Wellington apprentice to Henry Bellew to the age of twenty-one years, to be brought up in housewifry & found in meat, drink, apparel, lodging, hose, shooes & all things fit and necessary & at the end of term to discharge her well apparelled.

An indenture in the early 1700s had the Churchwarden Thomas WELLINGTON binding a poor parish apprentice until the age of twenty-one:

Indenture made on 6th June, eighth year of Queen Anne, A.D. 1709, between Thomas Wellington, Churchwarden, and Henry Bellow and William Morish, Overseers for Stockleigh English Parish, and Mary Pope, Widdow, have bound Joan Drew to Mary Pope till the age of twenty-one years to be brought up in huswifry.

Another indenture two years later, had Thomas WELLINGTON taking on a parish apprentice until the age of twenty-four. Joan and Elias DREW may have been from the same family and fell on hard times due to the death of a parent:

Indenture made 4th April 1711, tenth year of Queen Anne, A.D. 1711, between John Brown, Churchwarden, and John Bradford and William Blackmore, Overseers, Stockley English, and Thomas Wellington, Yeoman, of the said Parish and County (of Devon) have bound Elias Drew, Parish Apprentice, till the age of fower and twenty years in husbandry, Thomas Wellington providing for him and to discharge him at the end of term well apparelled.

Still another contract in 1742, had a James WELLINGTON taking on an apprentice for the parsonage. This one was quite firm in its conditions that the poor lad should no longer be a financial burden on the parish:

Indenture made sixteenth day of September, sixteenth year of George II., King, etc., A.D. 1742, between William Wyat, Churchwarden of Stockley English, County Devon, and William Wyat, and Robert Avary, Overseers, etc., bound John Pomeroy, Apprentice to James Wellington, for the Parsonage, until the age of twenty four years, the Apprentice to do as Statute requires. James Wellington to instruct or cause to be instructed in Husbandry work, and find him the said Apprentice, competent and sufficient meat, drink and apparel, lodging, washing, and all other things necessary and fit for an Apprentice, he not to be any way a charge to said Parish, or Parishoners of the same, and to save the aforesaid harmless and indemnified during the said term. At the end of term to provide the said Apprentice double apparel of all sorts, good and new, one for the holy days and another for the working days.

We know that our John WELLINGTON from Talaton completed his apprenticeship and became a qualified apothecary and druggist. He set up a chemist shop in Chard in Somerset and married Molly BOWDEN in 1772 at the age of 25 years.

He appears to have over-extended himself, as I found a notice in the Sherborne and Yeovil Mercury of 10 May 1773. John WELLINGTON, druggist of Chard – bankrupt. This turn of events may have been a contributing factor in his younger brother Richard’s elopement from his master one month later.

From my research at Devon Records Office I found Francis PYLE was a gentleman freehold farmer in Talaton. He held deeds for land and estates within the Hayridge Hundred during the late 1700s. Richard WELLINGTON would have been apprenticed in a trade on the estate or farm such as blacksmithing or husbandry.

Richard was totally reliant on the good will of his master. Fellow workers or members of the master’s family may have bullied the young man. He could have been mistreated, become very unhappy or homesick and have only one means of escape which was to run away.

At the age of 19, Richard was not the only apprentice to feel the need to spread his wings and experience some of life’s temptations. The Sherborne and Yeovil Mercury was a regional newspaper published in Dorset whose readership also included the counties of Wiltshire, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. During 1773 there were at least 40 notices posted by masters whose apprentices had eloped or run away.

By 1773, Richard had already worked at least 5 or 6 years as a farm apprentice with still another 2 years left to serve. He would have toiled long hours and resented his lack of leisure and personal freedom. He probably read about his eldest brother’s bankruptcy and set off to walk the 30 km to Chard to visit him. Or Richard might have longed for more excitement in his life and headed to the busy port of Exeter in the hope of gaining paid employment on a ship or by joining the navy.

If Richard did run away to sea (which is the most likely scenario) he made sure he was going to be “well apparelled”. I can find no further records on Richard WELLINGTON’s life after this notice so I don’t know if he ended up a sailor or returned to farming.

There is better news on his brother John WELLINGTON, the apothecary and druggist of Chard. It appears he traded his way out of bankruptcy, as a notice in the Sherborne and Yeovil Mercury on 26 September 1774 announced payment of a dividend to his creditors.

In 1777, after 5 years as a bankrupt, John was expanding his business and advertising for journeyman coopers and cabinet makers. It appears he learned from his early mistakes and went on to become very successful. He was the founder of a family dynasty of pioneering chemists in Devon and Somerset.

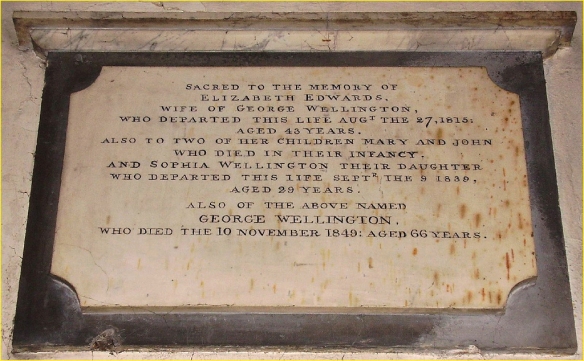

John WELLINGTON died in Chard in 1827, at the age of 79. Three of his children (John, George and William) were druggists and grocers in South Petherton, Yeovil and Chard. They were also respectable civic leaders, each holding office on their town councils.

[Sources: www.familysearch.org/Apprenticeship_in_England; Apprenticeship in England, 1600-1914, Joan Lane; Sherborne and Yeovil Mercury or Western Flying Post 1773-1778; index of adverts at this link]; Erskine-Risk, J. Apprenticeship indentures from Stockleigh English Parish Church. Trans. Devon. Assoc. vol. 33 (1901) pp.484-494. [Index].